In the remote South Pacific, on the rugged island of Tanna in what is now the nation of Vanuatu, one of the most fascinating and misunderstood religious movements of the modern era continues to endure.

Known as the John Frum Movement, it is often described as a cargo cult. That’s a term used by anthropologists to explain belief systems that arose when Indigenous societies encountered the overwhelming material power of industrialized nations. Yet to reduce the John Frum Movement to a curiosity or anthropological oddity is to miss its deeper meaning. At its heart, the movement represents a powerful response to colonialism, war, cultural disruption, and the sudden appearance and disappearance of unimaginable wealth during World War II.

Related: The ‘Cult of the Offensive’ was your grandfather’s ‘Violence of Action’

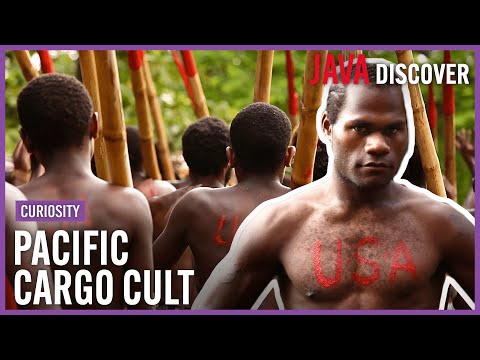

Each year on February 15, followers gather at Sulfur Bay near the smoking slopes of Mount Yasur, one of the world’s most active volcanoes, to celebrate John Frum Day. Dressed in improvised military attire, with USA painted across their chests, bamboo poles carried like rifles, and American flags raised high, participants reenact the rituals they believe will bring John Frum back and with him the cargo that once transformed their world.

To understand why this ritual endures more than 80 years after the war, one must return to the moment when the modern world arrived unannounced on Tanna’s shores.

Tanna Before the War

Prior to World War II, Tanna was largely isolated from global economic systems.

Its people lived according to kastom, a deeply rooted cultural framework encompassing traditions, rituals, land use, and spiritual beliefs passed down through generations. While European missionaries and colonial administrators had been present since the 19th century, their influence was uneven and often resisted. Christianity had gained a foothold in parts of the island, but many communities continued to practice traditional belief systems centered on ancestral spirits and the land itself.

Life on Tanna was subsistence based, communal, and cyclical. Material wealth was measured not in manufactured goods but in social relationships, land stewardship, and ritual knowledge. Tools were handmade, trade networks were local, and change occurred slowly. This equilibrium was violently disrupted in the early 1940s when the Pacific theater of World War II turned the region into a strategic hub.

Why the New Hebrides Mattered in the Pacific War

Although Tanna itself never became a massive base like Guadalcanal or Espiritu Santo, the island was part of the New Hebrides, a chain that proved crucial to American strategy in the Pacific Theater of Operations. Following the rapid expansion of Japanese forces across Southeast Asia and the Pacific in 1941 and 1942, the United States needed secure locations to halt Japanese advances and support the long campaign toward Japan.

The New Hebrides occupied a key position between the U.S. supply lines coming from Australia and New Zealand and the contested battle zones in the Solomon Islands. American military planners viewed the region as a defensive shield protecting Australia from invasion and as a logistical steppingstone for the Allied counteroffensive. Espiritu Santo, located north of Tanna, became one of the largest Allied bases in the Pacific, hosting airfields, naval repair facilities, hospitals, and massive supply depots.

From these bases, American aircraft, ships, and troops could be staged, repaired, and resupplied before moving north into combat zones such as Guadalcanal. The success of the Guadalcanal Campaign, often described as the turning point of the Pacific War, depended heavily on these southern support hubs. Without secure rear areas like the New Hebrides, sustained American operations in the Solomon Islands would have been nearly impossible.

Even smaller islands like Tanna were swept into this strategic web. Aircraft flew overhead, ships passed offshore, and personnel moved through the region. The war transformed the South Pacific into a vast interconnected system of bases, air routes, and supply chains, and Indigenous communities found themselves living alongside one of the largest military mobilizations in human history.

The Arrival of the Americans

When the United States entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the South Pacific became a vital staging ground for the Allied campaign against Japan.

Thousands of American troops passed through or were stationed on islands across Melanesia, including areas near Tanna. With them came an astonishing array of material goods such as canned food, vehicles, radios, weapons, clothing, medical supplies, and construction equipment. Airstrips appeared almost overnight. Ships unloaded mountains of crates filled with items the islanders had never seen before.

To the people of Tanna, this cargo seemed to materialize out of thin air. They observed American soldiers performing rituals such as marching in formation, raising flags, communicating with radios, and following strict routines, and then watching planes land with supplies. From an Indigenous worldview shaped by spiritual causality rather than industrial logistics, it was reasonable to assume that these rituals were directly responsible for the arrival of wealth.

Equally significant was the way American troops interacted with local populations. Compared to colonial administrators and missionaries, many U.S. soldiers were informal, generous, and less rigidly hierarchical. They shared food, tools, and stories. Some local men worked as laborers or guides, receiving wages and goods in return. For a brief moment, the people of Tanna experienced a material abundance unlike anything in their history and a glimpse of a world where power and prosperity seemed attainable.

The Mystery of John Frum

Out of this experience emerged the figure of John Frum, a name often interpreted as a variation of John from America. To followers, John Frum is not merely a historical soldier but a spiritual being, prophet, or ancestral force who foretold the arrival of the Americans and promised a future of abundance.

Accounts of John Frum vary. Some say he appeared in visions before the war, dressed in Western clothing, promising that the old ways of kastom would be restored and colonial rule overturned. Others describe him as an actual American soldier who befriended locals and spoke of returning one day. Still others believe John Frum resides within Mount Yasur, whose fiery eruptions are interpreted as signs of his presence and power.

What unites these interpretations is the belief that John Frum represents hope, justice, and material renewal. He is a symbol of resistance against colonial authority and missionary control, both of which had sought to suppress traditional practices. By embracing John Frum, followers asserted their cultural autonomy and reimagined modernity on their own terms.

The Birth of a Cargo Cult

Anthropologists later labeled movements like John Frum’s as cargo cults, a term that has since been criticized for its dismissive tone. While such movements involve rituals intended to attract material goods, they are also deeply political and spiritual responses to inequality. For the people of Tanna, the disappearance of American troops after the war was as shocking as their arrival. Almost overnight, the airstrips fell silent, the ships stopped coming, and the cargo vanished.

Faced with this sudden loss, followers reasoned that the rituals that had once brought cargo could bring it again. They began constructing symbolic airstrips, control towers, and antennas. They drilled in formation, mimicked military discipline, and raised flags. These acts were not naive attempts to summon airplanes but meaningful reenactments of a time when the world seemed to offer abundance and dignity.

Rituals and Symbolism

The rituals of the John Frum Movement are among its most striking features. Participants often wear minimal clothing, sometimes only traditional britches, blending kastom with military imagery. USA is painted boldly across their chests in white letters, symbolizing the source of the cargo and the perceived generosity of America. Bamboo poles serve as rifles, and handmade flags replicate the Stars and Stripes.

Marching is central to these rituals. Lines of men move in step, echoing the drills they observed during the war. This discipline is not merely imitation but devotion, an act of faith that order, unity, and belief will once again open the pathways to prosperity.

American flags hold particular significance. Raised ceremonially, they are treated as sacred objects, linking the movement to the era of abundance and to John Frum himself. To outside observers, this can appear ironic, but for followers, the flag represents a promise unfulfilled rather than loyalty to a foreign nation.

Teaching the Cultural Impact of WWII on Pacific Populations

As a U.S. history teacher for 11th-grade students, I use the John Frum Movement as a gateway to explore the broader cultural impact of World War II on Pacific populations. My students examine how the arrival of U.S. troops transformed the social, spiritual, and economic landscapes of islands like Tanna. We analyze firsthand accounts, photographs, and oral histories that show the scale of the cargo, the construction of military bases, and the interactions between soldiers and local communities.

Students engage in discussions about how these encounters disrupted traditional practices while also inspiring new belief systems, such as the John Frum Movement. I encourage them to consider questions like: How did the sudden arrival and withdrawal of military resources affect local hierarchies? What role did ritual, memory, and observation play in shaping Indigenous responses? How can the concept of a cargo cult help us understand the intersection of religion, colonialism, and global warfare?

Through interactive activities, including mapping exercises, students recreate the logistical networks of the Pacific Theater and the movements of soldiers and islanders. By connecting the historical context of WWII to living cultural practices, such as John Frum Day, students gain a deeper appreciation of how war reshapes societies beyond the battlefield. These lessons help them see history not as distant events but as lived experiences with ongoing consequences.

John Frum Day on February 15

The most important event in the movement’s calendar is John Frum Day, celebrated annually on February 15. Part religious service, part cultural festival, and part historical reenactment, the day draws followers from across Tanna.

The celebrations begin with ceremonial marches and flag raising rituals. Songs and chants recount the promises of John Frum and the coming return of cargo. Elders deliver speeches reaffirming faith in the movement and the importance of kastom. The atmosphere is both solemn and celebratory, infused with hope that this year or perhaps the next, John Frum will return.

John Frum Day is not only about waiting for cargo. It is also a reaffirmation of identity and a declaration that the people of Tanna will define their own relationship with the modern world. In this sense, the holiday functions as an annual act of cultural resistance as much as a religious observance.

Mount Yasur and the Sacred Landscape

The movement is geographically centered around Sulfur Bay near Mount Yasur.

The volcano’s constant activity, its glowing lava and thunderous eruptions, imbues the landscape with spiritual significance. Many followers believe John Frum resides within the volcano and that its eruptions are signs of his continued presence and power.

In Melanesian cosmology, the natural and spiritual worlds are deeply intertwined. Mountains, rivers, and forests are not inert backdrops but living entities connected to ancestral forces. Mount Yasur’s volatility reinforces the belief that powerful forces are at work, waiting for the right moment to emerge.

Colonialism, Christianity, and Resistance

The John Frum Movement also cannot be separated from the colonial context in which it arose. European administrators and Christian missionaries often viewed the movement as heretical, subversive, or even dangerous. Leaders were arrested, rituals were banned, and followers were pressured to abandon their beliefs.

Yet repression often strengthened the movement. For many followers, John Frum represented liberation from foreign rule and imposed religion. While Christianity emphasized obedience and spiritual salvation, John Frum promised material justice and the restoration of traditional values. The movement thus became a vehicle for expressing grievances against inequality and cultural erosion.

Persistence into the Modern Era

Today, Vanuatu is an independent nation, and Tanna is no longer isolated from the global economy. Tourists visit Mount Yasur, mobile phones are common, and modern goods circulate widely. Yet the John Frum Movement persists.

Its survival speaks to its adaptability. While few followers may literally expect cargo planes to descend tomorrow, the rituals continue as expressions of faith, identity, and historical memory. John Frum has become less about material goods alone and more about dignity, autonomy, and the right to interpret modernity through Indigenous values.

Rethinking the Meaning of Cargo Cults

Modern scholars increasingly challenge the simplistic portrayal of cargo cults as irrational misunderstandings of technology. Instead, they argue that movements like the John Frum Movement are sophisticated responses to sudden economic and cultural upheaval. They reflect an attempt to make sense of inequality in a world where wealth appears unevenly distributed and mysteriously controlled by distant powers.

Seen through this lens, the John Frum Movement is not a relic of the past but a living commentary on globalization, faith, and historical trauma. It asks enduring questions about who controls wealth, why prosperity arrives for some and vanishes for others, and how communities preserve their identity in the face of overwhelming change.

Marching Between the Past and Future

The image of men marching with bamboo rifles under the banner of USA may seem surreal, but it is rooted in lived experience and collective memory. For the people of Tanna, World War II was not an abstract global conflict but a moment when the heavens seemed to open and abundance poured down, only to be taken away again.

The John Frum Movement endures because it captures that moment and refuses to let it be forgotten. Through ritual, symbolism, and faith, followers continue to march not just for cargo, but for recognition, justice, and control over their own destiny. In doing so, they remind the world that history’s impact does not end when the soldiers leave, and that belief can be as much about memory and meaning as it is about miracles.

Don’t Miss the Best of We Are The Mighty

• Why the US used an island-hopping campaign in World War II

• The DoD has experience bombing volcanoes… for some reason

• How a volcano in Indonesia helped Napoleon get wrecked at Waterloo