During one of the final and most important sieges of the Civil War, a combination of racism towards black troops, concern for appearances, and sheer blinding incompetence and cowardice led to the bloody disaster that was the Battle of the Crater.

The Confederate Army was engaged in a last ditch defense of Petersburg, Va., the logistics and rail hub that supplied the forces defending their capital at Richmond, against the Union Army under command of General Ulysses S. Grant. Once Petersburg fell, the war was as good as over.

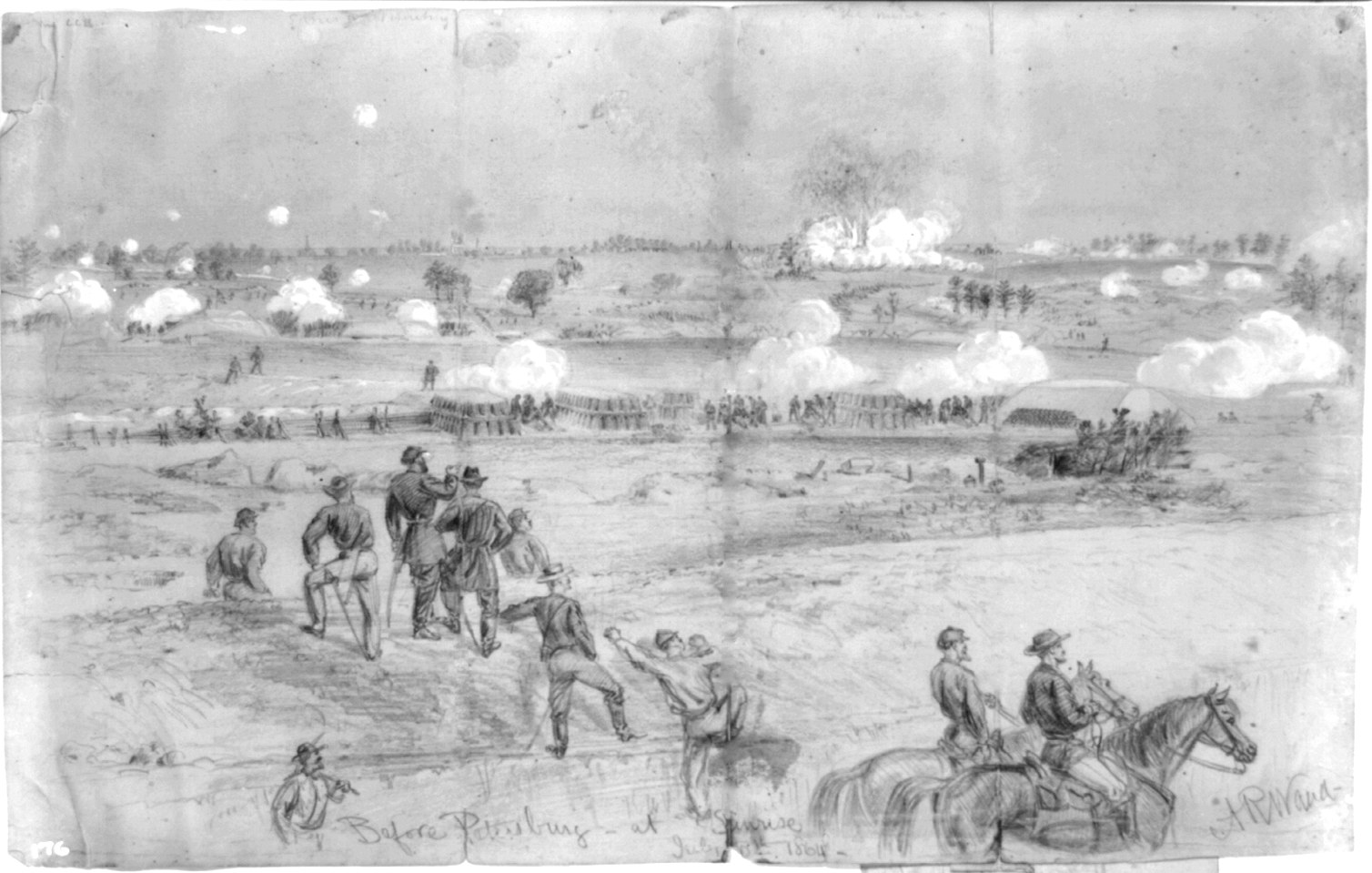

The siege had turned into trench warfare that presaged World War I. Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee’s mastery of field fortifications and defense in depth had made offensive operations by the Union against entrenched Confederate troops a terribly bloody endeavor. The siege was at a stalemate, and new tactics were called for.

The Union 48th Pennsylvania Regiment was largely drawn from coal country, and its commander, Col. Henry Pleasants, was convinced they could dig a long mine under the rebel lines and use blasting powder blow to a large hole in their fortifications. A four-division assault force would then seize the heights overlooking Petersburg, greatly shortening the siege. His corps commander, Gen. Ambrose Burnside, endorsed the plan.

The operation was conducted with a strange mix of brute force labor and a strategic lassitude from higher command, and suffered from a chronic lack of logistical support. Most of the Union leadership, from Grant on down, was skeptical of the plan, and saw it as a way to keep the soldiers busy at best.

The 4th United States Colored Troops (USCT) under Gen. Edward Ferraro was specially trained to lead the assault, specifically to flank the crater on both sides. But Gen. George Meade, commander of the Union Army at the battle of Gettysburg, thought little of the plan and the abilities of the black troops to carry it out.

He also voiced concerns to Grant that if the attack failed, it would look as if black soldiers had been thrown away as cannon fodder. Grant agreed, Burnside inexplicably had his division commanders draw lots, and Brigadier Gen. James Ledlie drew the short straw.

It was bad enough that the last minute change brought in badly unprepared troops for a tricky attack, but Ledlie had the distinction of being one of the most drunken cowards in the Union officer corps. This was to have terrible consequences.

Union troops operating north of Petersburg had drawn off most of the Southern troops, leaving the line weakened, and the time was ideal for the assault. After months of labor and the emplacement of more than four tons of blasting powder under the Confederate fortifications, the attack began with triggering the explosives at 4:45 a.m. on June 30, 1864.

The resulting blast was the largest man-made explosion in history up to that point. A massive mushroom cloud, which sent men, horses, artillery, and huge amounts of earth flying into the air, left a crater 130-feet long, 75-feet wide, and 35-feet deep. The explosion killed a full third of the South Carolina unit defending the strongpoint, over 200 men, in an instant. The concussive force of the explosion left the rest of the brigade stunned for at least 15 minutes.

Despite the spectacular success of the mine blast, the assault started to go wrong from the beginning. Ledlie was drunk and hiding in a bunker in the rear, and his leaderless division ran into the crater instead of around it, milling about uncertainly. Other units pouring into the attack only added to the chaos.

The recovered Confederate troops laid a kill zone around the crater, keeping the Union troops pinned down, and fired everything from rifles to mortar shells into the packed troops stuck in the blast zone. The 4th USCT, despite being relegated to the second wave, penetrated farther than anyone, but suffered severely in the process.

After holding out for hours, a final counterattack by a Confederate brigade of Virginians routed the still numerically superior Union forces, which suffered appalling casualties, and many were taken prisoner.

There are many Southern eyewitness accounts of black prisoners being summarily shot down by Confederate troops, and the particularly severe casualty rates suffered by the black units seem to bear this out. Even some Union soldiers were reportedly involved in the killings, driven by fear of the Confederate warnings of reprisals for fighting alongside black soldiers. The shouting of “No Quarter!” and “Remember Fort Pillow!” by the black troops during their charge was also later cited as a justification for the executions by the Confederacy.

Burnside and Ledie were both relieved of duty after the disaster, though Burnside was later cleared by Congress since it was Meade who decided to replace the USCT at the last moment. Burnside never held a significant command again.

The supreme irony of the battle was that despite the efforts to spare the lives of black troops from politically inconvenient slaughter, the utter failure of the lead wave to force the breach lead to terrible casualties for the black units they had replaced. Gen. Grant later said “it was the saddest affair I witnessed during the war.”

The siege would drag on for another eight months, and Petersburg’s fall led to the prompt surrender of Richmond, precipitating Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Courthouse. The Crater remains a prime example of a brilliant plan spoiled by incompetent execution.