On Aug. 1, 1944, less than two months after D-Day, Marine Maj. Peter J. Ortiz, five other Marines, and an Army Air Corps officer parachuted into France to assist a few hundred French resistance fighters known as the Maquis in their fight against the Germans. Ortiz had already worked and trained with the Maquis in occupied France from Jan. to May 1944. The mission, Operation Union II, faced a rough start. Due to the danger of the Marines being spotted or drifting away from the drop zone, the jump was conducted at low altitudes.

“Because of the limitations, we had to make this jump at 400 feet,” said Sgt. Maj. John Bodnar in a Marines.com interview. “As soon as we were out of the aircraft our chutes opened and the next thing I remember is I was on the ground.”

One Marine’s parachute, that of Sgt. Charles Perry, failed to open. At such low altitudes, using a reserve wasn’t an option, and Perry was killed when he hit the drop zone. Another Marine was injured too badly to continue. The four Marines able to perform the mission were Ortiz, Sgt. Jack Risler, Sgt. Fred Brunner, and Bodnar who was also a sergeant at the time.

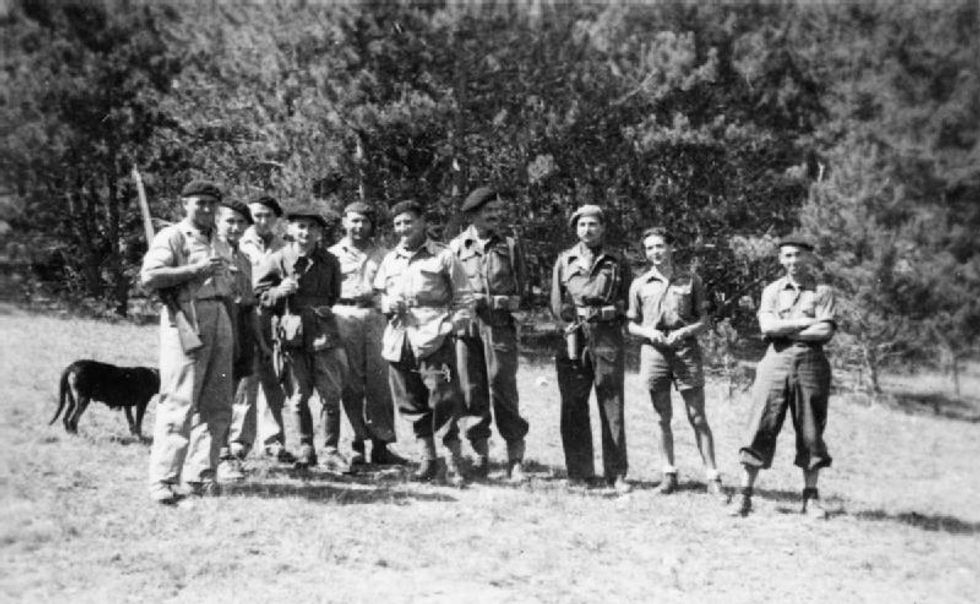

The Marines, some of the only ones to serve in the European theater in World War II, would make good use of the personnel they had. First, they recovered 864 supply crates of weapons and ammunition that were dropped after the men parachuted in. Then, they linked up with the Maquis and began training the resistance fighters.

For a week, the Marines schooled the resistance fighters on how to use the new equipment, how to conduct ambushes, and how to harass German forces. They also conducted reconnaissance and mapped prime areas to conduct ambushes.

When the fighters began conducting the ambushes, they were very successful. The exact casualty counts are unknown, but the Maquis and their Marine handlers inflicted so much damage so quickly that German intelligence believed an allied battalion had jumped in to assist the resistance instead of only six Marines and a soldier.

The Germans did not take the threat lightly. They remembered Ortiz from the Jan.-May 1944 mission and were still angry about his theft of 10 Gestapo trucks and a pass that let him drive the vehicles right through checkpoints. They began executing captured resistance members in public areas in an attempt to deter others. On Aug. 14, an entire town was murdered after the Germans found injured resistance members hiding in the church.

The Marines were on a nearby ridge and watched as the Germans destroyed the town.

“They burned the place down,” Bodnar later said in a Marines.com interview. “We just left there … they killed them all.”

The next day, the Marines were trying to move positions when a German patrol got the jump on them. They split up and tried to escape, but Ortiz, Risler, Bodnar, and a resistance member were pinned down. Fighting in a small town, Ortiz became worried that the Germans would destroy it if the Marines escaped. After his initial calls for a parley were ignored, he simply walked out while under fire to speak to the German commander.

The German finally ordered his men to stop firing and Ortiz, fluent in German, French and a few other languages, offered to surrender himself and his men if the Germans would promise to leave the town alone. The German commander, believing he was fighting a company, agreed.

Risler and Bodnar stepped out and the Germans captured the resistance member, Joseph Arcelin. Luckily for the Arcelin, he was wearing the uniform of Sgt. Perry and so the Germans didn’t execute him. Maj. Steven White, a Marine Corps intelligence officer and liaison to the 60th Anniversary Commemoration of Operation Union, said the Germans thought the Americans were lying about their numbers.

“Initially, the German officer was in disbelief,” White told Marines.com. “He did not believe that only 4 Marines had held off his forces for this long. He insisted that Maj. Ortiz turn over the rest of his team members.”

Ortiz was able to convince the German officer that the four men formed the entire team. He and his men spent the rest of the war in a German POW camp near Bremen, Germany.